Positive phase 3 trial results, have raised hope among scientists that the effectiveness of lecanemab is the first step toward finding a cure for Alzheimer’s disease. After decades of research resulting in drugs available to ease the symptoms, lecanemab is the first drug to reverse the disease itself. Some scientists, however, have urged caution and downplayed the effectiveness of the drug.

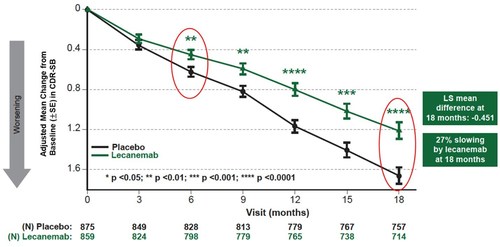

On Tuesday evening, the results of phase 3 clinical trials of lecanemab were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. 1,800 people aged between 50 and 90 participated in the study all of whom had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. They received the drug or a placebo intravenously every fortnight. Scientists reported a 27 per cent slowing down in memory loss over an 18-months period. In those taking lecanemab or a placebo, the disease still progressed but at a much slower rate in those receiving the drug.

The breakthrough treatment is an antibody treatment working to remove amyloid, the toxic protein associated with the disease. Amyloid damages brain cells and brings on memory loss and difficulty in communication.

In the study, researchers rated the severity of Alzheimer’s in participants by measuring symptoms such as forgetfulness while also assessing problem-solving skills and the ability to live independently. To determine the amyloid levels in the brain, scientists carried out brain scans and blood tests. They discovered that in many trial participants who’d been given lecanemab, amyloid levels had dropped below the Alzheimer’s disease threshold.

Reactions to the results have been predominantly positive. Speaking to the Guardian, the director of the UK Dementia Research Institute at University College London, Bart De Strooper said:

“This is the first drug that provides a real treatment option for Alzheimer’s patients.

“While the clinical benefits appear somewhat limited, it can be expected that they will become more apparent over time.”

The director of UCL’s Dementia Research Centre, Professor Nick Fox echoed his sentiments:

“I believe it confirms a new era of disease modification for Alzheimer’s disease. An era that comes after more than 20 years of hard work on anti-amyloid immunotherapies.”

In the UK, Alzheimer’s disease is the most prevalent dementia cause and among the leading causes of death in Britain. Caring for people with the disease costs the UK economy approximately £25 billion annually with this figure set to have doubled by 2050.

UK Alzheimer’s Society reaction

The UK Alzheimer’s Society published its comments on the lecanemab report on its website. Associate Director of Research at Alzheimer’s Society, Dr Richard Oakley wrote:

“Our research led by Sir John Hardy over thirty years ago seeded trials like this by discovering the importance of amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease. It laid the foundations for billions of pounds of investment into many of the drugs like lecanemab, with 117 other drugs currently in trials.

“There is still a long way to go before we could see lecanemab available on the NHS, and we await clarity for how and when the approval process will take place in the UK, and whether regulators believe it is cost-effective. We mustn’t forget that lecanemab can only be given to people with early Alzheimer’s disease who have amyloid in their brain. This means people with other types of dementia, or in the later stages of Alzheimer’s disease, can’t benefit from this drug.”

Alarm among some scientists as two trial participants pass away

Some scientists have voiced their concerns over the safety of the drug after a second trial participant died. Although the manufacturers have refuted claims that the two deaths are related to the drug, questions as to how widely regulators should make it available have arisen.

A 65-year-old woman passed away after suffering from a massive brain haemorrhage, some linked to lecanemab. After her death, her husband engaged Northwestern neuropathologist Rudolph Castellani who also studied Alzheimer’s disease, to carry out an autopsy and determine the cause of death. In the co-authored report, Castellani concluded that many of the woman’s brain blood vessels had been surrounded by amyloid deposits. Taking lecanemab every fortnight had likely weakened and inflamed the blood vessels and directly or indirectly lead to her severe brain haemorrhage. Similar circumstances existed in the death of the first person to die while participating in the lecanemab trial.

Castellani told science.org after receiving permission from the woman’s husband to publicly speak about his wife’s case:

“There’s zero doubt in my mind that this is a treatment-caused illness and death. If the patient hadn’t been on lecanemab she would be alive today.”

Castellani’s views are his own and do not represent Northwestern’s position.